By Ashli Akins

“Why the heck are you bringing your javelin with you to Kenya?” my friend laughed at me. Another just said, “Okay, I don’t even want to know why.”

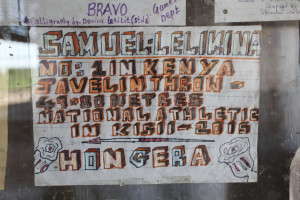

It all started over a year ago, when I stumbled upon a blog post by Ian Mungai, PA-MOJA’s field coordinator, who told the unbelievable story of Samuel, a Maasai boy from PA-MOJA’s sister school – Uaso Nyiro Primary School – in central Kenya, who became the national javelin champion despite only ever throwing with sticks. He only had access to real javelins in competition.

I spent grades 1-12 at the Langley Fine Arts School, one of the sister schools that supports PA-MOJA, and the key base for its volunteers and Board of Directors. This project was therefore already close to my heart, but Samuel’s story touched something within me that was much rawer.

I immediately posted a comment in response to the blog post last July:

“Wow! Samuel’s story holds a special place in my heart, as someone who… dreamed of being an Olympian with all my heart… I still have my javelin. If I make my way to Kenya, perhaps I can bring it and give it to Samuel! May he continue to follow his dreams.”

Unbenownst to me at the time I wrote the comment, my work took me to the African continent only a few months later to coordinate an international workshop on arts-based approaches to intercultural conflict resolution.

“So, you gonna bring your javelin?” a friend asked, out of the blue.

I had completely forgotten. At first, I laughed at her. There was no way. I was leaving the next day, and would be traveling for a month from Canada to South Africa before even arriving in Nanyuki, Kenya. But quickly the dreamer in me took over. Why not?

* * *

As a child, I created Olympic rings out of left-over Cheerios and plastered my walls with heroes like Jackie Joyner-Kersee. I read every book about Jesse Owens and memorized every factoid about the history of the Olympic games. By attending the Langley Fine Arts School – a public school that specialized in the arts – I was taught discipline, passion, and creativity during the day, only to rush off to track practice by 4 pm each afternoon. I trained and competed six days per week, from age 9 to 18. I excelled in throwing – discus, hammer, and javelin – competing in the BC Summer Games and the US National Junior Olympic Championships.

But despite my well-crafted dreams, my body had different plans. I fell ill, and eventually had to quit track and field, letting go of my Olympic dream. Though it took years of rehabilitation, both psychological and physical, to re-carve my dreams, I found my own Olympics, through a life of service and a career in international human rights. The courage, will, and determination that this childhood dream taught me remains tangible to this day. I still cry when watching Cool Runnings (yes, I admit, my favourite movie), track competitions, or even Olympic commercials.

The catalyst to my courage – that which allowed me to persevere beyond adversity to pursue my passion against all odds – was that someone believed in me. Someone believed I could accomplish my dream, no matter how ridiculous, unconventional, or unlikely it seemed. And this is what connected me to Samuel’s story – and why my javelin had to reach him. So that he knew that someone who had never even met him believed he could do it, despite all odds.

Harold Willers is the unspoken hero of this story. He was my track coach, who not only coached me for years in Abbotsford and Chilliwack, but who also mentored me to become an adult with courage and hope. He supported me through hospital visits, tests, and an operation, and believed in me when I geekily idolized Olympians. His coaching methods were not to intimidate, but to encourage, and this is something that I have taken to heart in my teaching and supervision.

After a fire had burnt the warehouse down at our track club, this javelin was one of the only remaining objects in tact, having survived because of its metal shaft. But during the fire, a small bobbin had loosened inside, making it no longer viable for competition, so Harold gave it to me, knowing I couldn’t afford one myself. To him, it was simply a practical use of an unwanted javelin. To me, it meant someone believed in me.

My lofty dreams are the same reasons I have kept all of my throwing implements over a decade later, despite no longer being a competitive (or even an amateur) thrower. My hammer, discus, and shot put (and, until now, the javelin) remain tucked away in storage at my brother’s house in Victoria. They had once meant the world to me, traveled the continent with me, and brought me intense pain and joy. While they deserve much more than a dusty closet, they also deserve more than simply being discarded as a chapter of my former life – the javelin is the first to find its new home.

* * *

And so, the day before my flight, I decided to bring my javelin with me from Victoria, BC, to Nanyuki, Kenya.

And so, the day before my flight, I decided to bring my javelin with me from Victoria, BC, to Nanyuki, Kenya.

My brother packed it in his 1982 two-door Saab, but his car broke down, leaving us on the side of the highway late at night with a javelin. How would I get this thing to Kenya, if we failed in Step One?

Step Two involved last-minute errands by foot, since Victoria’s public transit wouldn’t allow me to board the bus with a giant spear. I walked into London Drugs to refill my prescriptions, only to receive many confused looks.

At the Harbour Air seaplane terminal, I was told the javelin was too long for the tiny seaplane; it just physically would not fit no matter how much I begged. I frantically called all of the island’s courier services with 20 minutes to spare before my flight to Vancouver, finally finding one (Dan Foss) who was willing to pick up the unwrapped javelin from the float-plane terminal and take it directly to my front door in Vancouver, within 24 hours, for only $22. The catch: my flight to South Africa was in 22 hours. It was a gamble that I was willing to take – and the only chance I had left.

The next day, I packed, attended my final class at UBC, and came home to find the javelin waiting for me at my doorstep. My partner, Trent, frantically wrapped it in left-over pizza boxes and bright-yellow duct tape, before we headed to the airport, with javelin in tow. We crammed it through the open window of a tiny Car2Go, tripped fellow Skytrain passengers on public transit, and finally arrived at the YVR airport.

The next day, I packed, attended my final class at UBC, and came home to find the javelin waiting for me at my doorstep. My partner, Trent, frantically wrapped it in left-over pizza boxes and bright-yellow duct tape, before we headed to the airport, with javelin in tow. We crammed it through the open window of a tiny Car2Go, tripped fellow Skytrain passengers on public transit, and finally arrived at the YVR airport.

The Air Canada representative was impressed by our disheveled commuter efforts, and wrapped the javelin in Canadian National Ski Team plastic before sending it on its international mission.

The Air Canada representative was impressed by our disheveled commuter efforts, and wrapped the javelin in Canadian National Ski Team plastic before sending it on its international mission.

A day later, I arrived at the Cape Town airport and waited at the baggage carousel until all of the bags had disappeared. I was the only one left. The javelin never showed up. I went to the oversized sports-gear section, but it wasn’t there either. My heart sank. I asked at the customer service desk about my missing piece of luggage. She questioned why I was transporting a javelin. Was I competing? “No, it’s for a kid named Samuel,” I responded, distracted by its disappearance. I told her the story. She then made it her entire life’s mission in that moment to find my javelin, radioing to her colleagues about this lost piece of extremely important luggage.

She questioned why I was transporting a javelin. Was I competing? “No, it’s for a kid named Samuel,” I responded, distracted by its disappearance. I told her the story. She then made it her entire life’s mission in that moment to find my javelin, radioing to her colleagues about this lost piece of extremely important luggage.

It was found, headed somewhere in the wrong direction on the tarmac.

The javelin and I then squished into a taxi to Stellenbosch, where it sat in my room for a week while I coordinated the workshop, before coming back to the Cape Town airport to finally travel to Nairobi, Kenya. The Kenya Airways’ regulations clearly stated that all luggage, including sporting equipment, had to be under seven feet. (The javelin was 7 feet 2 inches.)  My only hope was to find a service representative who would eyeball its measurements, rather than be a stickler for rules. Success; it was off to Kenya!

My only hope was to find a service representative who would eyeball its measurements, rather than be a stickler for rules. Success; it was off to Kenya!

When the javelin came out on the other side, I shepherded it through the chaotic mess of the post-airport-fire make-shift customs area (in a parking garage, instead of at the airport). The customs official questioned the large throwing implement that I was bringing into his country, but allowed it.

My friend, Judy, picked me up at the airport and stored the javelin at her house in Nairobi for the next week, before it traveled with Steve (our driver) and I for four hours to Ol Pejeta Conservancy, its penultimate stop before meeting Samuel.

* * *

The day had finally come. We piled into the conservancy truck to drive to Samuel’s school, where the school’s headteacher, Mr Isaac, his deputy Mr. Nyingi, another school head and “The Big Five” were waiting for us.  (The Big Five are the Samburu boys from this school who, despite all odds, went to the national championships. Samuel then won gold in the javelin.) There were also a couple of younger student-athletes present, who clearly dreamed of being part of The Big Five someday.

(The Big Five are the Samburu boys from this school who, despite all odds, went to the national championships. Samuel then won gold in the javelin.) There were also a couple of younger student-athletes present, who clearly dreamed of being part of The Big Five someday.

I told the story of this resilient javelin, who survived a fire before being gifted to me over 15 years ago, and who crossed an ocean and thousands of kilometres to get here. The boys shared with me their victories and dreams as athletes, and the directors told me a bit about Samuel’s humble family background, filled with adversity.

Samuel’s smile radiated through his shy demeanor, as his knee-high red socks made him seem even taller than he already was.

Samuel and I unwrapped the javelin and tested it out. I was forced to embarrass myself with the first throw, before Samuel threw it across the schoolyard like it was a ping-pong ball shot out of a catapult.

The boys were curious about the different throwing technique that I had learned in Canada, compared to their Kenyan technique, and requested a brief lesson. The event quickly turned into a lively competition; by the time we had to leave, we left the boys and their teachers in the field, still throwing the javelin over and over and over again.The utter joy and friendly competition that quickly arose was worth the journey in itself.

The event quickly turned into a lively competition; by the time we had to leave, we left the boys and their teachers in the field, still throwing the javelin over and over and over again.The utter joy and friendly competition that quickly arose was worth the journey in itself.

This is Samuel’s first javelin – the first time he gets to practice with something other than a stick, and the beginning of what looks to be an extremely promising athletic career for a student-athlete who has already exceeded all expectations. He chose a sport that spoke to his heart, even if it was unheard of in his village and virtually impossible to pursue. He possesses the determination, humility, courage, and perseverance to make his Olympic dreams come true. All I asked was that, if he makes it, he invites me as his guest.

This is Samuel’s first javelin – the first time he gets to practice with something other than a stick, and the beginning of what looks to be an extremely promising athletic career for a student-athlete who has already exceeded all expectations. He chose a sport that spoke to his heart, even if it was unheard of in his village and virtually impossible to pursue. He possesses the determination, humility, courage, and perseverance to make his Olympic dreams come true. All I asked was that, if he makes it, he invites me as his guest.

Ashli, thank you for sharing this remarkable and inspiring story!

Love that you just followed your intuition, laughing on the way.