[two_third]

The PA-MOJA logo began with the desire to match our vision of a world where people and wildlife are equally valued and co-exist in a mutually beneficial way. We wanted a simple logo that included an unlikely pairing of a child touching Sudan, the last remaining male Northern White Rhino in the world. Langley Fine Arts photo teacher, Donna Usher, created our first drawing and sent us with the challenging task to take a picture of a small child next to a rhino.

When we found out that German documentarian, Frank Feustle, was at the Ol Pejeta Conservancy filming the story of a young “rhino whisperer” named Newton Mwangi, we jumped at the chance to join them for the day so we could take a few pictures.

At the time of these photos, Newton Mwangi was a student at Irura Primary. He was chosen to work with the filmmakers because of his high grades and his keen interest in wildlife. On this particular day, Frank was filming Newton standing beside Sudan. In order to keep the nervous three-ton animal from knocking Newton flat, one of the guards, Patrick Mureithi, rubbed Sudan’s belly while constantly replenishing the pile of alfalfa hay that was keeping him relatively content. Newton was shy but enthusiastic as we asked him to assume a variety of poses alongside his favorite animal.

Newton and the rhino, who had every reason to fear each other, looked as symbiotic as a boy and his dog, except that Newton weighs less than 100 pounds while Sudan weighs over 5000.

Both Sudan and Newton have won a few of life’s lotteries but challenges remain. Although Sudan is pampered and protected and his horns have been painlessly removed in order to protect him from poachers, he is still vulnerable as the remaining stumps have enough value to make him a target. His skin, as thick as tires, appears bullet-proof. It isn’t. An AK-47, popular with poachers, could easily finish him off.

Newton’s father operates a matatu (passenger van) and his mother works the family farm which borders the wildlife conservancy. Newton’s middle class family will be able to see him through high school; however, the majority of young people in his community can not afford the books, uniforms and school fees to make it past grade eight.

Most farmers in the community see little value in the wild animals that border their farms. Baboons and elephants often cross over the conservancy fence and destroy their gardens. The electric fences protecting the wildlife keep the farmers’ livestock from rich grazing land. Although Newton and many of his neighbors understand the importance of wildlife in attracting tourist dollars, they and their families need to eat today.

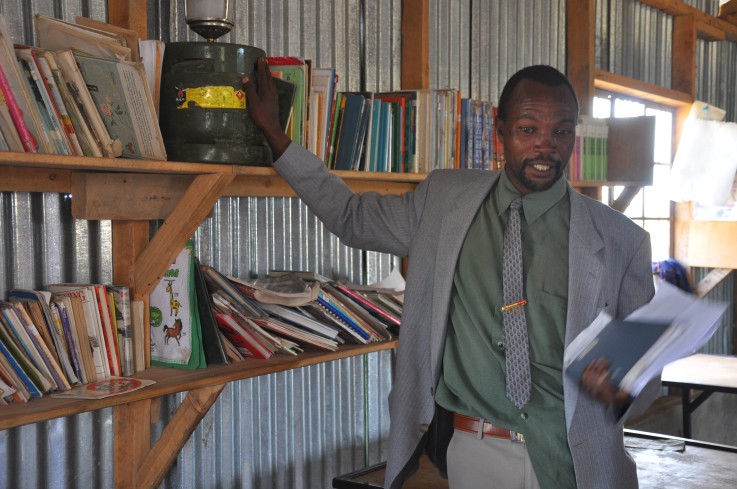

In response, local farmers and the Ol Pejeta Conservancy have recognized the need to cohabit with wildlife by blending and sharing limited resources. PA-MOJA was created in 2005 to support that effort by providing bursaries and building classrooms, libraries, and biogas stations in the community surrounding the conservancy. When farmers’ children can afford to go to school and learn in classrooms that have solid walls and floors, they are more willing to support Sudan as well as the black rhinos, elephants, hippos, lions, leopards and cheetahs that safely roam the Ol Pejeta Conservancy. Students like Newton have the opportunity to go to school and learn about the importance of wildlife in their own country. They share this information with their parents and elders who have influence in the community.

It’s too late for the Northern White rhino species. Sudan, his daughter Najin and grandaughter, Fatu will be the last. Education is the best hope for the rest of the endangered animals in Kenya and Africa.

[one_third_last]

New in highschool, leadership and Karate[/one_third_last]